October 25, Billy Barty’s birthday, is a great day to commemorate LPA milestones. In April 1957, Billy used his celebrity as an entertainer to draw 21 people representing nine states to the first national convention in Reno, Nevada. However, “Midgets of America” was rejected as the organization’s name and replaced by “Little People of America.” A dictionary committee was formed to contact all dictionary manufacturers for the purpose of correcting the inaccurate definition of the word “midget.” And therein is the first LPA milestone.

Want to subscribe to receive blog updates sign up today!

From the outset, LPA welcomed internationals, but only as honorary members. Yet Billy Barty was a willing consultant to LP organizations forming in 1968 and 1969 in Australia and New Zealand, for example. However, it took 25 years before LPA hosted in Washington, DC the first international conference for little people. The April 1982 conference goal to improve the quality of life for little people globally was advanced when 80 delegates representing eight countries attended.

In July 1982, as the alien resident spouse of LPA President Robert Van Etten, I did not meet the criteria for a foreign-affiliate membership. As a result, a bylaw amendment to allow permanent resident aliens to become LPA members was proposed and approved.

The achievement of two more LPA milestones.

The essence of LPA was evident from inception. For example, at the 1957 convention a Telephone Booth Committee was formed to lobby Bell Telephone Company for booths reachable by people of 48 inches. In 1960, LPA planned to publicize equal employment opportunity for little people and committees were formed to provide education scholarships and adoption support.

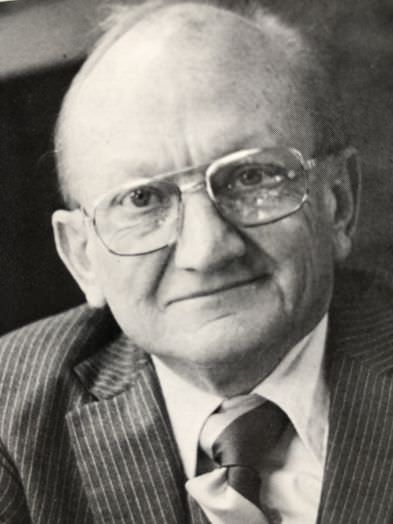

Although LPA was originally incorporated as a nonprofit organization exempt from paying taxes, donors could not take a tax deduction for contributions. As the eighth person to serve as LPA President, Robert Van Etten believed LPA’s future growth depended on becoming a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt organization. He was sure LPA’s educational, medical, and charitable activities qualified the organization for this status. And he was right. In 1984, together with the LPA Tax Exemption Committee he had appointed, Robert led LPA to another milestone event. LPA members at the St. Louis conference voted yes to amend the LPA charter and bylaws to align with IRS tax-exempt legal standards. And on October 28, 1986, the IRS granted interim approval for LPA’s section 501(c)(3) tax-exemption followed by final approval on December 31, 1989.

The first annual LPA conference held outside the United States was in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico in July 1985. This milestone week was memorable—the airlines lost our bags for two days, we got dripping wet from hot temperatures during the day and daily downpours at dinner time, and Robert and I took turns getting Montezuma’s revenge. Yet despite some discomfort, the conference was a huge success and the catalyst for the formation of an LP organization in Mexico. The highlight of Robert’s week was parasailing off the beach. The highlight of my week was watching him land on the beach. This post is informed by the 25th anniversary LPA Souvenir Book published by the Billy Barty Foundation in July 1982 and by excerpts from Always an Advocate, Part I, Volunteer Leadership Challenges, chapters 1 and 2. For the rest of the story, buy your e-book or paperback copy at https://www.amazon.com/dp/1737333600/